LISTEN:

NEW! Listen to an audio version of a provocative chapter as Brent Green answers a difficult existential question:

“How Small Are We?“

READ:

Can Someone’s Courage to Face Suffering Strengthen Us?

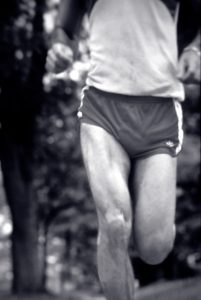

Dappled sunlight spilled upon the forested trail where we ran, and I felt elation seeing Dr. Mark Crooks pulling ahead, effortlessly. Though disabled with a single lung and suffering, he could trounce me on the trail. As his wide shoulders and a dark mane of wavy hair shape-shifted into elm tree shadows ahead, I reflected upon self-empowered living that he embodied.

He was a proud man who had learned too much about cancer, pain, and rehabilitation. When we jogged that spring day, he had already survived cancer for fifty-five years, battling nerve, thyroid, and lung cancers. He would face two more metastatic bouts—prostate and liver—before it would be over.

Cancer imposed egregious injustices upon an athlete and former Marine, who had earned a doctoral degree in exercise physiology and had dedicated many years to inspiring and teaching stricken men how to recover from heart attacks. Mark’s first mitochondrial mutation had followed a head-and-neck X-ray in infancy: an untested therapy unwisely deployed by a physician to fight an antibiotic resistant sinus infection. Then a sarcoma appeared on his neck at age eight.

But I knew his mind well after three decades of friendship. He wasn’t thinking about the injustice of metastatic disease. He was thinking about a beautiful day—fresh air, sweet scents of budding trees, and his daily mastery over inertia. He wasn’t trying to intimidate me with superior conditioning either. Mark just ran far and away in the manner he chose to spend part of each day. His only unbeatable competitor was the nemesis lurking within since childhood. Early immersion in mortality propelled his life course and had given him the uncommon determination to fight evil with science, experimentation, and risk-taking.

Most lives cannot be summed up by a single incident; rather, most human stories are collections of actions and reactions, an amalgam becoming a narrative, of plots and subplots spanning decades. This narrative was also true for Mark’s story, but in one oddly defining moment, he leaped from the apex of a bridge crossing a dangerous river, plunging ten stories and landing in nine feet of coffee-colored water.

As he launched into the void from the lip of that bridge, an eighteen-wheeler blasted by him. Wind draft pushed his torso forward, introducing the possibility that he would land imperfectly and break his back. Then in midair, he mounted an invisible bicycle and pedaled for the finish. His body became vertical within a free-fall reaching sixty-three miles per hour, and he slipped splash-less into choppy, murky currents. Seconds later he exploded through the surface, arms extended in Olympic victory.

Jumping from a bridge into a river did not define Mark, but that single courageous act of fitness and determination illuminated his incandescent spirit while elaborating his message: humans can achieve greater wellness by taking calculated risks.

His risks were bold and brash; the doctor became his experiments. He did not advocate for mere mortals to follow in his jump stream. He saw risk as relative: one man’s Arctic Circle trek is another man’s casual day hike; one woman’s skydiving freefall is another woman’s tethered zip-line. The risk lies more in the heart of the actor than in the act itself.

Endorphins are a gift for taking risks: opiate pretenders that can reduce pain and create well-being, and, according to some authorities, become the biochemicals of longevity. Those same neurotransmitters had also molded an image of contentment that I witnessed in a super-athletic, one-lung man leaving me to follow his footprints in the damp loam of a Kansas running trail.

Whether swimming 375 miles nonstop in the frigid Missouri River from Kansas City to St. Louis for five grueling days or scaling the exterior of the tallest skyscraper in the Midwest (with no prior technical climbing experience), Mark commanded intense focus with each selected feat. He pushed himself forward with wisdom succinctly articulated by Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th-century existentialist: “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” That which did not kill Mark made him stronger, and he gained strength with leaps, dives, and near-misses.

Following our final run together, Mark shared his thoughts on aging, disease and decline, an unholy triumvirate that had visited him much too young when compared with most of his peers. “I still have a warrior mentality,” he said. “I’m a fighter. My whole life has been about overcoming things. Adopting fitness as a way of life and part of your daily regimen will keep you more mentally stable.

“I still feel that the best of my life is yet to come. I have certain optimism because I don’t realize the limitations that most sixty-three-year-old men have.”

His hourglass emptied two years later within the solitude of the Kansas City Hospice. Even then he pushed an intravenous cart around the corridors for glorious minutes of independent movement. Though death was at his doorstep, he still defied mortal inevitability, a diminished man but a noble spirit unwilling to submit until left no further options. Maggie Callanan, a wise and tenured hospice nurse and coauthor of “Final Gifts,” acknowledges the purpose and possibilities of this terminal patient’s elaborated final months, weeks, and days: “Instead of a last-gasp sprint, death can be a marathon.”

Mark Crooks, PhD, died on July 8, 2010. He finished life on his terms. He prevailed for decades over disease, depression, and disinterest. He found satisfying self-expression through running shoes and countless T-shirts drenched with sweat. And he defied aging, not to deny the inevitable but to thwart its pace, a warrior to the end.

Mark showed me another way to negotiate suffering. He personified one of the “beautiful people” described by hospice pioneer, Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross: “The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of those depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen.”

Mark showed me another way to negotiate suffering. He personified one of the “beautiful people” described by hospice pioneer, Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross: “The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of those depths. These persons have an appreciation, a sensitivity, and an understanding of life that fills them with compassion, gentleness, and a deep loving concern. Beautiful people do not just happen.”

He was an intellectual who invested time and scholarship in understanding the recurring cancers that haunted him throughout his adult life. He could speak to medical professionals in their language, citing the most recent clinical research about the treatment of his diseases. He often turned inward through meditation and self-reflection to manage fear and overcome inevitable uncertainties that come with competing and often ambiguous medical choices. He embraced wellness principles and alternative therapeutic modalities to supplement care he received from traditional western medicine. And, he was spiritual in ways I did not expect from a man so grounded in the here and now, so vigorous and athletic, so macho, such a pioneer in the life-affirming field of wellness.

I recall another time when I visited Mark during one of my speaking engagements in the Kansas City area. We had just finished a healthy meal: large, sumptuous salads composed of ingredients circumnavigating a bountiful garden, vegetables showcasing the colors of a rainbow. Healthy organic stuff. He asked me quite plainly if I believed in God. I answered with an equal directness that I did believe although I was not involved in a denominational church tradition at that period of my life, such as the Protestantism that had baptized me in the Christian faith and characterized my childhood. I asked the same question of him: “How about you? Do you believe in God, Mark?”

Mark opened his heart. He said he felt the presence of the Holy Spirit almost every waking moment of his life. He often had conversations with God as he jogged, which almost always involved running along trails bisecting forests near his home. He knew God was nearby; he knew there would be eternal life after life, and he felt God’s grace even as he had to face much uncertainty and so many medical procedures as a perpetual cancer victim.

I recall profoundly feeling moved by Mark’s declaration of his deepest spiritual feelings. I did not expect to hear statements of faith from a long-term friend who had never spoken to me before about God’s goodness and his earnest optimism about a conclusion of his suffering after the end of his life. I had always thought of him as tough, virile, a man’s man, grounded in the daily challenges of providing for his family and being a thought leader in the field of wellness. I felt honored and humbled that he trusted me enough to reveal these most private aspects of his spiritual life. With his declaration of faith, communicated with the certitude of a scientist, I too felt a presence of the Holy Spirit hovering over the dining room table as Mark helped me understand what he saw in his heart.

During the many years of our relationship, I felt great empathy for my friend, as one form of cancer after another emerged to challenge him. I felt sympathy for his suffering that surely clawed at his daily routines, always active and busy, but he rarely verbalized complaints while courageously challenging his archenemy. He met pain and physical decline with 600-calorie workouts; he discarded anxieties somewhere along innumerable running trails; he faced death by running through life at full stride.

I also felt confidence that Mark knew what to do to participate actively in his treatments and rehabilitation, and that he would prevail. I didn’t give up believing this until he could prevail no more—and then I knew in my heart that God would welcome Mark to eternal life and His grace. I believe Mark is sometimes with me now as I work out, inspiring me to run a little faster or lift more weight. Mark whispers to me when no one else can hear, “Make the world your gymnasium, Brent.”

Mark’s courage will always be a benchmark in my life as inevitable old-age illnesses and physical decline become nuisances during my final years and months. Like Mark, I plan to push IV carts defiantly in front of me and keep moving until I cannot move anymore. I plan to keep my running shoes tied until the end.

Questions about learning from the suffering of others

Who has inspired you to face suffering with greater courage and determination and why did this person influence you?

When pain invades your life, how would you ideally like to handle the discomforts, anxieties, and uncertainties?

Have you known someone like Mark Crooks who took on suffering as if a test of will and a challenge to defeat?

What have you learned about suffering from others that you could share with your children and grandchildren to instruct them about resilience and courage in the face of sickness and disease?

How would you now like to prepare yourself better to face suffering that could inspire and instruct others you love?

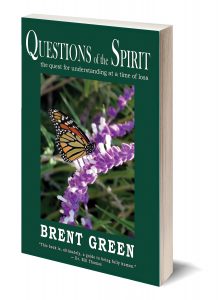

Available on Amazon. Click here.

We’d love your help spreading the word about Questions of the Spirit. Please share this book and website with your contacts on LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter.